It was when my son was aged three that it started. “Bugger, bugger, bugger,” he would say when he was at nursery, at church and out and about on the bus. “I can’t think where he learnt it from,” I remember saying with exaggerated puzzlement when I regaled a friend with this tale. “It must be from his father.”My friend, who knows my mild-mouthed husband well and has also worked with me through many decades, said: “Let’s face it, Jo. It could have been a lot worse.” And sure enough, it didn’t take long before worse – a lot worse – it got.

What should a mum do about swearing?

What is a mother to do? Do I tell my son it’s unacceptable to swear and forfeit pocket money whenever a foul word leaves his lips? Does that mean I have to clean up my own act? Do I want to do that? Could I? Do I tell him it’s sometimes acceptable for adults, but never for children? It’s OK in private, just not in public?

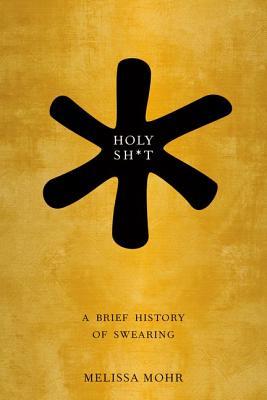

Cue Melissa Mohr and Holy Sh*t, a Brief History of Swearing… How I wish she had written it before.

This is an utterly delightful book. It’s beautifully written, witty and in many places laugh-out-loud funny. It’s also a serious book. She looks her subject matter square-in-the-face. Mercifully, she never resorts to being silly or coy, though she does acknowledge her own sensitivity to taboo and the words she herself finds hard to write down.

Swearing has a history

Mohr looks at the history of swearing, as in taking oaths (that’s the “holy” bit of the title) and at obscenities, those emotive words that tend to remind us we have bodies (that’s the “sh*t” bit).

She traces their stories, from Roman times, through to the Bible, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Eighteenth and Ninet eenth Centuries right up until the present day, looking at how oaths and obscenities have evolved and how they are related to the culture of the day. It claims to be a brief history but it seems pretty thorough to me.

eenth Centuries right up until the present day, looking at how oaths and obscenities have evolved and how they are related to the culture of the day. It claims to be a brief history but it seems pretty thorough to me.

It’s worth reading for the chapter on the Bible alone. I learnt a great deal from that and not just about swearing. For example, Mohr asks the question – why does God swear? Every word God says is true, so why does he say to Abraham: “By myself I have sworn” in Genesis? And why does God command us to swear by him: “The Lord your God you shall fear; him you shall serve, and by him alone you shall swear.” (Deut 6:13)?

Mohr explains the role of swearing is related to the establishment of monotheism. In the Hebrew Scriptures, God was one of hundreds of gods a person could worship and so he was in a quest to establish himself as the one true God.

Swearing is a key weapon in this campaign. When you swear by God, you acknowledge that he is omnipotent; he is the one that can see your actions, hear your words. If you swear by Baal, you acknowledge his omnipotence instead. That is why God asks his people to swear by him and why he swears himself to them, by way of example.

Taking oaths is a tool to establish monotheism

The taking of oaths, which is still part of our legal system and government today, is rooted in that tool to establish monotheism that goes right back to the days of Abraham. How interesting. (Well, that’s one way of putting my response. What I actually thought was “Blimey!”)

And while we’re talking fascinating anecdotes, listen to this. Mohr takes us on a hilarious romp through the use of euphemism in the Hebrew Bible. She says it never refers to the genitals when hand, foot, side, heel, shame, leg or thigh will do.

Eve is made from Adam’s penis

She then quotes the scholar Ziony Zevit, who argues that, in the Genesis narrative, Eve is actually made out of Adam’s penis, in particular from his penis bone. Most mammals have a bone in their penis, a baculum, which helps with erections. Humans, spider monkeys, whales and horses don’t, but the other species can’t achieve erections through blood pressure alone and have a baculum to assist.

Zevit claims that the ancient Israelites would have known about anatomy, being familiar with skeletons, and would have known men and women have the same number of ribs. Zevit thinks that in this story, the word “tesla” often translated as “rib” is actually a euphemism for genitals, as it so often was. What the story really means is that Eve was made from Adam’s penis. The baculum was taken from him and used to create his companion, thus in one neat myth you explain where women came from and why men don’t have penis bones.

Is swearing good or bad?

But enough of these tit-bits, I’m sure that what you really want to know is whether swearing is a good or a bad thing and how embarrassed we should be feeling when our children start saying: “Bugger.” (If indeed other people’s children do.)

Mohr does have a view, but she restricts her opinions on the rights and wrongs of using obscene language to the introduction and the epilogue. I am grateful to her for that. I am also grateful to her because through reading her entertaining history, I found myself developing my own thinking , so now I feel confident and robust in what I am passing on to my child.

When my boy was aged six, he came to me and said: “Mum. I really want to swear. Can I? Will you be cross with me?” I said: “That depends. Is it one of those occasions when only a swear word will do?”

“Yes,” he said.

“In that case,” I replied. “Swear quietly and make sure you don’t repeat it outside this house.” He came over and whispered in my ear: “F***ing Mrs Stapleton!”

And he was absolutely right.

- A version of this review appeared in Third Way.