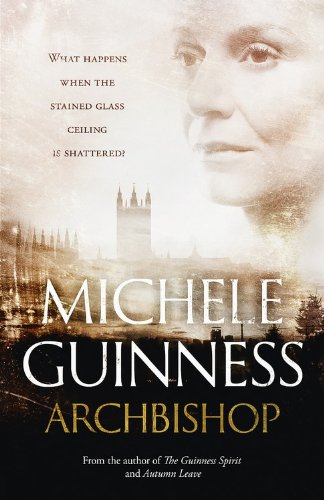

Well, that’s a good idea for a book: Archbishop is about the first female Archbishop of Canterbury. It’s fiction, obviously.

The tale is set in the future. In the world that Michele Guinness creates, The Church of England admits women to the episcopacy in 2014 (I wish). Vicky Burnham-Woods becomes Bishop of Larchester in 2016 and Archbishop of Canterbury in 2020.

The tale is set in the future. In the world that Michele Guinness creates, The Church of England admits women to the episcopacy in 2014 (I wish). Vicky Burnham-Woods becomes Bishop of Larchester in 2016 and Archbishop of Canterbury in 2020.

Vicky is charismatic, successful in growing churches and deeply committed to bringing the church back into the heart of the community. She is thoroughly committed to defending the poor and not afraid to fight the government on social justice and welfare reform.

Interestingly, the prime minister at the time of Vicky’s appointment is a gay man but Vicky, despite being radical as far a social justice is concerned, is conservative around marriage and not sympathetic to clergy wanting to conduct gay marriages. This wins her some enemies. She has enemies in other places too.

As the novel unfurls, it becomes clear that somebody is trying to undo her. Press photographers have an uncanny knack of knowing exactly where she is, even in her most private moments. Tit bits of her past are leaked to the press in an attempt to undermine her.

Who is it that is doing this? Is it one of her friends? Is it a member of her staff? Are they working with the prime minister? Or with those bishops who were utterly opposed to her appointment on the grounds of her sex?

It’s a great story – or at least it should be.

The problem with Archbishop is that it isn’t the page-turner that it could have been. I confess to having found it grindingly slow – all 543 pages of it. It’s very well researched but it isn’t well enough written. The characterisation is poor, the dialogue unbelievable and the story-telling somewhat cumbersome.

Let’s start with the research. Guinness clearly knows and understands the Anglican church. The historical references are accurate, the way in which the media behaves is convincing and the window into the NHS (Vicky’s husband, Tom, is a surgeon) is well portrayed.

I would love to say the skulduggery she describes could never happen amongst a community of Christians – but alas I know better. There are many of us who are very familiar with that being nice to your face whist stabbing you in the back. Guinness gets the Church of England and portrays it very well.

Indeed, one of the features of the novel that hindered my enjoyment was the very accuracy with which the church was portrayed. It was so depressing. Who would want to spend their leisure time filling their head with the machinations of the Anglican church? Not me.

So full marks to Guinness on research. Few could have done it better.

Unimpressive characterisation

The characterisation is less impressive. It would be unfair to say that Vicky is a caricature – she is far more than that – but the way she is depicted is a little “thin” nonetheless. I would have hoped that an Archbishop of Canterbury would have had a richer and deeper inner life than Vicky appears to have. In the very last scene, Vicky and Tom whisper their marriage vows to each other before falling asleep. Vicky seems too twee, too emotionally immature, to have reached the highest ecclesiastical office. I never quite believed in her enough to care greatly about what happened.

Which brings me to the story-telling. The narrative is developed through back-story. The novel starts in 2019 with the Crown Nominations Commission discussing who to put forward for the post of Archbishop of Canterbury. From there, there is a flipping to and fro between what is happening in the present and the events of the past, helpfully indicated with subheadings: February 2020, 2006, 2020, 1983 and so on.

I didn’t find this confusing – but for those who do, there is a chronology in the form of Vicky’s CV at the back (don’t wait until you get to the end to find it) – but I did find it tedious. I reached the point where I just wanted to skip the back-story and wished Guinness had done the same.

Covering too many bases

I think Guinness is attempting to cover too many bases in this novel. There is nothing wrong with a slow story – nothing at all. If a novel has got beautifully portrayed characters that seem more real than your own flesh and blood, it doesn’t if they don’t get anywhere very fast.

Guinness starts many of the chapters with a quote from the German theologian, Jurgen Moltmann, who is Vicky’s seminal theologian. A different kind of novel, would be one in which the theology of Moltmann is integrated into the tale, making it into a fiction that illuminates theology and vice versa. Again, if a novel like that was done sufficiently well, the speed at which the story unravels would not important.

But I don’t think Guinness is displaying the skills, in this text, to write a novel that can afford to be slow. She is probably a very good writer of non-fiction but a mediocre writer of novels. (It’s the weakness of the dialogue gives that brings me to that conclusion.) In which case, she needs to keep the reader interested by spinning a great yarn. And she could do that. The plot is great. If she had just made a decision to tell the story twice as fast, I might have enjoyed it.

- This review first appeared in Third Way magazine.